Abstract

Water is a vital yet increasingly scarce resource that transcends national boundaries and presents both challenges and opportunities for international diplomacy. This paper examines water as a geopolitical issue, exploring its dual potential to trigger conflict and foster cooperation among nations. Drawing on international legal frameworks and case studies-including the Nile River, Indus Basin, and Mekong River- this article analyzes how hydro-diplomacy is being used to manage tensions and promote peace. The paper argues for an integrated, multi-level approach that leverages legal norms, institutional mechanisms, and technological innovations to transform water into a tool for sustainable collaboration.

Keywords: Water diplomacy, Transboundary rivers, Hydro-politics, International law, Conflict resolution, Sustainable development

1. Introduction

Water, often dubbed “blue gold,” is at the heart of human survival, ecological sustainability, and economic development. As global demand for freshwater increases and climate variability threatens supply, water security is emerging as a defining challenge of the 21st century. The complexity intensifies in the case of transboundary watercourses, which cross political boundaries and demand cooperative governance. With over 260 international river basins globally (UNESCO, 2015), effective water diplomacy is critical in averting conflicts and fostering peace.

This paper explores the role of diplomacy in managing shared water resources. It examines the drivers of water-related disputes, the role of international legal frameworks, and successful institutional models. Through case studies and analysis, the paper aims to present a holistic understanding of how diplomacy can mediate the growing tensions over water.

2. The Geopolitics of Water

Water-related tensions often arise in regions where political instability and hydrological stress intersect. A prime example is the Nile River Basin, where Ethiopia’s Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) has become a flashpoint. Ethiopia claims sovereign rights to harness the Blue Nile for development, while downstream Egypt fears significant disruptions to its water supply (Yihdego, Rieu-Clarke, & Cascão, 2017). A similarly complex situation exists between India and Pakistan, two nuclear-armed rivals whose cooperation over the Indus River Basin is governed by the 1960 Indus Waters Treaty (IWT). Despite geopolitical volatility, the treaty has endured, demonstrating the potential for structured diplomacy to facilitate stability (Pohl et al., 2014). However, in recent years, political tensions have led to calls for re-negotiation, reflecting the fragility of even long-standing water-sharing agreements.

2.1 Results and Discussion

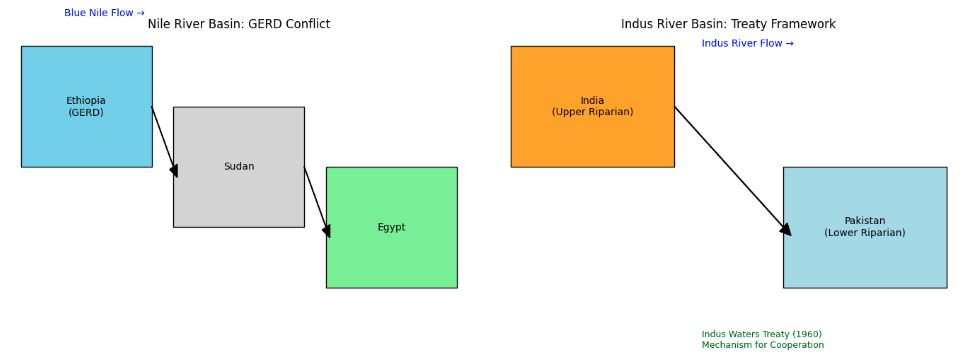

Water-related geopolitical tensions are intensifying in regions where hydrological stress overlaps with political instability. The data indicates two prominent and complex cases of transboundary water disputes: the Nile River Basin and the Indus River Basin. Both cases exemplify how water can act both as a source of conflict and a catalyst for cooperation, depending on the regional political context and institutional frameworks.

Fig. 1 Geopolitics and water

2.2. The Nile River Basin

The Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) represents a critical pivot in East African geopolitics. The results show Ethiopia’s pursuit of hydropower and economic development has triggered diplomatic frictions with downstream countries, notably Egypt. Ethiopia asserts its sovereign right to utilize the Blue Nile, arguing that GERD will bring substantial benefits to the region, including electricity generation and regional integration (Yihdego, Rieu-Clarke, & Cascão, 2017). However, Egypt, heavily reliant on the Nile for its freshwater supply, perceives the dam as an existential threat. The political discourse surrounding GERD reflects a clash between development ambitions and historical claims over water resources. Notably, despite multiple rounds of negotiations, there remains a lack of a legally binding agreement, indicating deep-seated distrust among riparian states and the weakness of regional water governance mechanisms.

2.3. The Indus River Basin

Conversely, the Indus River Basin-shared by India and Pakistan-demonstrates the potential resilience of institutionalized water-sharing frameworks. Governed by the 1960 Indus Waters Treaty (IWT), this case reveals how formalized agreements can buffer geopolitical shocks. Despite several military conflicts and ongoing tensions, the IWT has largely held firm, facilitating data sharing, dispute resolution, and regular communication between parties (Pohl et al., 2014). However, recent political escalations have led to calls within India to revisit or even revoke the treaty. This suggests that while treaties can stabilize water-sharing relations, they are not immune to the broader geopolitical environment. As such, the IWT’s durability may ultimately depend on continued political will and evolving regional power dynamics.

2.4. Comparative Insights

Comparative analysis reveals that institutional robustness, historical precedent, and power asymmetries play central roles in determining the trajectory of water-related conflicts. The Nile Basin, lacking a comprehensive and enforceable treaty, remains volatile, with diplomacy frequently stalling. In contrast, the Indus Treaty offers a structured mechanism for dispute mitigation, though it too is vulnerable to erosion under sustained political pressure. These cases highlight the need for adaptive governance structures that incorporate hydrological realities, equitable benefit-sharing, and multilateral dialogue.

Ultimately, transboundary water governance requires more than technical coordination; it necessitates sustained political engagement, trust-building, and flexibility in the face of environmental and geopolitical change.

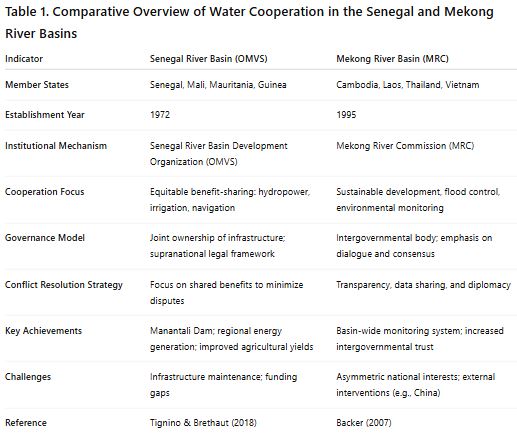

3. Water as a Catlyst for Cooperation

Although water has conflict potential, it also possesses a unique ability to unify. Shared water challenges require collaborative problem-solving, often leading to enduring institutional partnerships. For example, the Senegal River Basin Development Organization (OMVS) enables Senegal, Mali, Mauritania, and Guinea to equitably share benefits such as hydropower, irrigation, and transportation infrastructure (Tignino & Brethaut, 2018). This model prioritizes benefit-sharing rather than simple water allocation. Another notable case is the Mekong River Commission (MRC). Created through the 1995 Mekong Agreement, the MRC brings together Cambodia, Laos, Thailand, and Vietnam to coordinate sustainable development and avoid conflict. Despite differing national interests, the MRC has enhanced dialogue and transparency (Backer, 2007), showing the importance of institutional frameworks in water diplomacy.

3.1. Results and Discussion

The analysis of transboundary water cooperation initiatives reveals that water, despite its potential to spark conflict, more often serves as a powerful catalyst for regional collaboration. Case studies from the Senegal River Basin and the Mekong River provide compelling evidence that shared water resources can foster sustained, institutionalized cooperation among nations.

In the case of the Senegal River Basin, the Senegal River Basin Development Organization (OMVS) illustrates how water can underpin long-term collaboration. Formed by Senegal, Mali, Mauritania, and Guinea, the OMVS emphasizes equitable benefit-sharing rather than rigid water allocation. This approach has enabled member countries to jointly invest in and manage hydropower, irrigation, and transportation infrastructure (Tignino & Brethaut, 2018). Notably, the shared benefits model helps mitigate conflict potential by aligning national interests around mutual gains, reinforcing the value of integrative institutional mechanisms.

Similarly, the Mekong River Commission (MRC), established by the 1995 Mekong Agreement, provides a framework for Cambodia, Laos, Thailand, and Vietnam to coordinate water development while avoiding conflict. The MRC’s emphasis on dialogue, data-sharing, and inclusive decision-making has improved transparency and trust among member states (Backer, 2007). Though challenges remain—such as asymmetries in political and economic power-the MRC has contributed to a relatively stable and cooperative governance environment across the Lower Mekong Basin.

These findings suggest that cooperative institutions, when underpinned by principles of equity, communication, and mutual benefit, can transform water from a source of tension into a tool for diplomacy and regional integration. The focus on benefit-sharing, rather than strict water quotas, appears particularly effective in promoting durable collaboration. This has significant implications for water-scarce regions globally, where climate stressors and population growth are intensifying the need for cooperative water governance.

4. Legal and Institutional Foundations

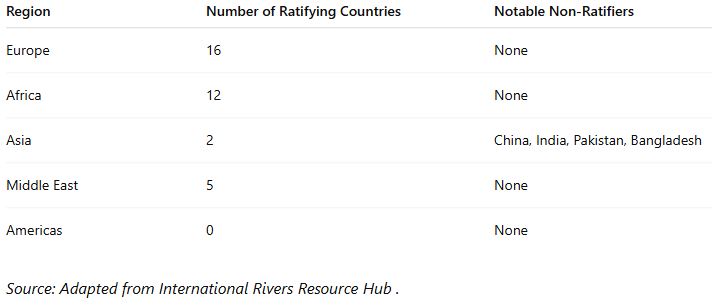

Legal frameworks underpin successful water diplomacy. The UN Watercourses Convention (1997) sets out guiding principles like equitable and reasonable use and the obligation not to cause significant harm (McCaffrey, 2001). However, its limited ratification restricts its influence, particularly in politically sensitive basins.

The role of multi-track diplomacy-where states, civil society, and knowledge institutions collaborate-has gained prominence. The Geneva Water Hub exemplifies this approach, integrating legal expertise, conflict mediation, and scientific knowledge to address water-related disputes (Geneva Water Hub, 2016). These multi-level mechanisms are increasingly essential for adaptive governance in complex water systems.

4.1 Results and Discussion

4.1.1. Ratification Status of the UN Watercourses Convention

The UN Watercourses Convention (1997) establishes key principles such as equitable and reasonable utilization and the obligation not to cause significant harm to other riparian states. However, its limited ratification hampers its global impact, particularly in politically sensitive regions like South Asia.

Table 2: Ratification Status of the UN Watercourses Convention

The absence of major Asian countries like China, India, and Pakistan from the list of ratifying states is particularly concerning, given their significant roles in transboundary water governance. For instance, China and India share several major rivers, yet they have not committed to the Convention, which could facilitate more cooperative management of these shared resources.

4.1.2. Challenges in South Asia

In South Asia, the lack of ratification of the UN Watercourses Convention has led to fragmented and often contentious water governance. For example, Bangladesh and India share 54 transboundary rivers, but only the Ganges has a formal water-sharing agreement. The absence of a comprehensive legal framework has resulted in disputes over water allocation, such as those concerning the Teesta River (bonikbarta.com).

4.1.3. Role of Multi-Track Diplomacy

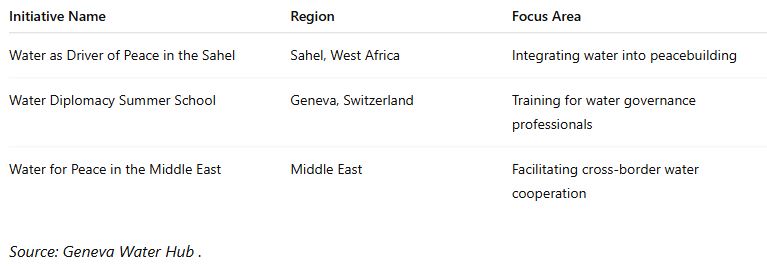

In response to the limitations of formal legal frameworks, multi-track diplomacy has emerged as a vital approach to water governance. The Geneva Water Hub exemplifies this strategy by integrating legal expertise, conflict mediation, and scientific knowledge to address water-related disputes. Their initiatives, such as the “Water as Driver of Peace in the Sahel” dialogue, demonstrate the effectiveness of collaborative efforts in mitigating water-related tensions (genevawaterhub.org).

Table 3: Geneva Water Hub Initiatives

4.1.4. Importance of Legal and Institutional Foundations

The interplay between legal frameworks and institutional mechanisms is crucial for effective water governance. While the UN Watercourses Convention provides a foundational legal basis, its limited adoption necessitates the development of regional agreements and institutions. For instance, the Indus Waters Treaty between India and Pakistan, despite its challenges, serves as a model for bilateral water agreements. Similarly, the Danube River Protection Convention has facilitated cooperation among European countries (icpdr.org; https://www.eco-business.com/)

In conclusion, while the UN Watercourses Convention lays the groundwork for international water law, its limited ratification underscores the need for region-specific agreements and the adoption of multi-track diplomacy to address the complexities of transboundary water governance.

5. Challenges and Opportunities

Several obstacles hinder water diplomacy. Power asymmetries among riparian states often lead to unilateral actions, as seen in the GERD conflict. Furthermore, the impacts of climate change—such as glacial melt, droughts, and floods-compound the difficulty of achieving consensus.

Yet, the future holds promise. Technological innovations in hydrological data sharing, remote sensing, and real-time monitoring can enhance transparency and build trust. Integration of water management into global development frameworks, like the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG 6), provides a normative foundation for cooperation.

6. Conclusion

Water diplomacy is both a necessity and an opportunity in our increasingly interconnected and water- stressed world. While competition over transboundary waters can provoke tensions, they can also drive dialogue, innovation, and peacebuilding. The evolving discipline of hydro-diplomacy underscores the need for robust institutions, equitable legal norms, and inclusive governance to turn water into a bridge rather than a barrier. As climate and demographic pressures intensify, water diplomacy must evolve into a central pillar of international relations.

References

Backer, E. (2007). The Mekong River Commission: Problems and prospects. Danish Institute for International Studies.

Bonik Barta. (n.d.). Teesta River Dispute and Water Sharing Challenges in South Asia. Retrieved from https://www.bonikbarta.com

Eco-Business. (n.d.). Regional Cooperation on River Basins and Environmental Governance. Retrieved from https://www.eco-business.com

Geneva Water Hub. (2016). A Blue Peace: A new approach to managing water as an instrument for peace and cooperation. Retrieved from https://www.genevawaterhub.org/ [

Click to access gowp_rapport_wwweng_final_0.pdf

International Commission for the Protection of the Danube River (ICPDR). (n.d.). The Danube River Protection Convention. Retrieved from https://www.icpdr.org

McCaffrey, S. C. (2001). The law of international watercourses: Non-navigational uses. Oxford University Press.

International Rivers Resource Hub. (n.d.). Table 2: Ratification Status of the UN Watercourses Convention. Retrieved from https://www.internationalrivers.org

Pohl, B., Kramer, A., Hull, W., Blumstein, S., & Michel, D. (2014). The rise of hydro-diplomacy: Strengthening foreign policy for transboundary waters, adelphi.

Tignino, M., & Brethaut, C. (2018). Water law and cooperation mechanisms in Africa. In M. Tignino & C. Brethaut (Eds.), Research handbook on freshwater law and international relations (pp. 251-266). Edward Elgar Publishing.

UNESCO. (2015). Water for a sustainable world – The United Nations World Water Development Report. Paris: UNESCO.

Yihdego, Z., Rieu-Clarke, A., & Cascão, A. E. (2017). The Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam and the Nile Basin: Implications for transboundary water cooperation. Water International, 42(4), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508060.2017.1336449